In high-throughput warehouses and factories, the robots are the easy part to notice. The hard part is what you don’t see: the moment-by-moment decisions that keep dozens, or hundreds, of mobile robots from colliding, idling, or clogging the same corridor. That’s why Robot Control System (RCS) software has become a core layer in modern intralogistics. It sits where business intent turns into robot action—turning orders into executable tasks, allocating work across a fleet, and keeping traffic moving when real life refuses to follow a neat plan.

For teams evaluating automation, the question is rarely “Do we need robots?” It’s “How do we run robots at scale without chaos?” A well-scoped RCS answers that question with centralized task assignment, scheduling, and route planning—while also handling the messy bits like access control, elevators, and exception monitoring that separate demos from production reality.

What Is an RCS, Really—and Why Does It Matter?

Is RCS just “fleet management software” with a new name?

In many deployments, “AMR fleet management software” and “RCS” get used interchangeably, but the intent is consistent: an RCS is a centralized system that manages task assignment, robot scheduling, and route planning for infield logistics robots.

The value shows up as soon as you have competing constraints. A forklift-capable robot might be the only one that can place a pallet into racking. A tote-moving robot might have higher speed but cannot interact with a dock door. A cart-moving robot might need to coordinate with a staffed workstation that has its own rhythm. An RCS is the layer where those constraints become rules—then become decisions—then become measurable outcomes.

Where does an RCS sit in the system architecture?

A practical way to frame it is upstream and downstream responsibility. Externally, an RCS often operates as a downstream system to the order system, undertaking order processing in the form of task generation and execution control. Internally, it coordinates with the operating environment—like access control and elevators—to support full-area traffic automation. It also provides queue exception monitoring and efficiency statistics so operations teams can manage performance rather than guess at it.

This is why RCS discussions naturally overlap with WMS, WCS, and WES conversations: people are trying to draw clean boundaries. In real projects, the boundary you care about is this: what system decides “what should happen next,” and what system decides “how robots execute it safely and on time.” The RCS belongs to the second category, even if it also influences the first by providing constraints and feedback loops.

Why RCS Projects Fail in Real Facilities (And How to Prevent It)

“We bought robots, but throughput didn’t move”

This is common when teams treat dispatching as a simple “send robot A to point B” problem. In production, travel time is rarely the bottleneck. Congestion is. Poorly controlled intersections, narrow aisles, shared elevators, and human crossings create micro-delays that compound. A dozen 10-second stalls in an hour becomes a couple of lost robot-hours in a shift. Multiply that by fleet size, and the ROI you modeled gets shaved down fast.

A strong robot traffic control layer is what prevents that erosion. It’s not glamorous, but it is decisive: right-of-way rules, dynamic rerouting, reservation zones, and deadlock prevention are the difference between a fleet that “moves” and a fleet that produces.

“Everything worked in week one, then exceptions piled up”

Exceptions are not edge cases; they’re daily operations. A pallet is wrapped differently. A staging lane is full. A worker blocks a safety zone. A battery dips sooner than expected. If exception handling is manual and scattered, you end up running a robot fleet like a call center: constant interruptions and constant triage.

This is why exception monitoring and queue management must be built into the core control layer, not bolted on later. When your RCS treats exceptions as first-class objects—categorized, routed, and tracked—you create repeatable recovery. When it does not, every incident becomes a bespoke fire drill.

The Core Capabilities Buyers Actually Need (Beyond the Marketing Words)

Task orchestration that matches how work really flows

In real sites, tasks are rarely single-hop. A pallet might move from receiving to quarantine, then to storage, then to a value-add station, and finally to shipping. The handoffs matter. So does conditional logic. If a lane is full, the task should branch. If a station is down, the task should reroute. If an urgent order drops, the task priority rules must change without breaking everything else.

That is why “task orchestration” is more than a UI feature. It is a model of your facility’s operating logic. When your RCS supports flexible task flow arrangement for complex scheduling, you can adapt without constantly rewriting integrations.

Multi-robot coordination in mixed fleets

Many facilities start with one robot type and end up with several. The moment you run mixed fleets—tote robots, pallet movers, autonomous forklifts, conveyor-top robots—you need shared traffic logic and consistent mission semantics. Otherwise, each fleet becomes its own island, competing for the same physical space.

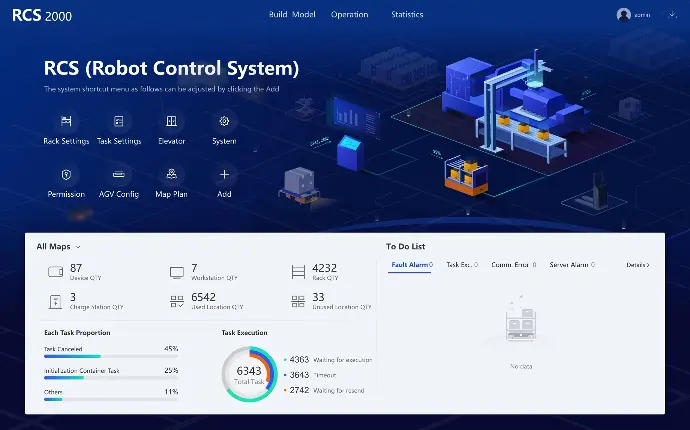

RCS-2000 is designed to support mixed scheduling of multiple AMR types, which is critical when different robot classes must share corridors, intersections, or docking resources.

Scale is not a slogan; it’s a set of system behaviors

Scalability is often presented as “supports X robots,” but what matters is how the system behaves under load: task assignment latency, route recomputation frequency, and the ability to maintain stable traffic rules when conditions shift.

On the RCS-2000 product page, Wesar describes cluster operation capability such as accommodating 1,200+ robots in one map and assigning tasks to 1,000 AMRs in one second, alongside support for 300 different AMR models performing tasks. These figures are not just “big numbers.” They hint at architectural decisions: the system is built to keep control decisions fast even as fleet size grows.

If you want to see that positioning directly, review the RCS-2000 Robot Control System page.

A Field-Tested Implementation Approach (Actionable, Not Theoretical)

Start with a map that represents constraints, not just geometry

Operations teams often underestimate how much “map modeling” drives performance. A clean map is not simply accurate walls. It encodes policy: one-way lanes, speed-limited zones, yielding points, no-go areas, and buffer zones near people-heavy workstations. If your first map treats every corridor the same, you’ll end up compensating with manual rules later.

A practical benchmark is this: if you cannot explain why robots slow down near a workstation, why they queue at a choke point, and how they behave when the queue exceeds capacity, the map model is incomplete.

Define station behavior like a contract

Robots fail at stations more often than they fail in transit. The reason is simple: stations are where physical interfaces and business rules meet. Pallet pickup requires pallet detection and alignment. Drop-off may require handshake with a conveyor or a door interlock. A station may have staffing windows. It may also have rules like “no two robots can wait here” or “only one robot can occupy this zone while the door is open.”

In practice, the best teams define each station with a contract: entry conditions, success conditions, timeout behavior, and exception routing. That clarity reduces “mystery failures” later.

Treat elevators and access control as first-class integrations

Multi-floor automation is where many projects hit their first major complexity wall. It’s not the elevator itself; it’s the coordination: reserving elevator time, enforcing priority, preventing two robots from contesting the same call, and managing what happens when an elevator is out of service.

Wesar describes RCS as communicating and interacting with access control and elevators to complete full-field traffic automation.

In practical terms, that means your RCS should coordinate “permission to proceed” and “permission to enter” events the same way it coordinates intersection reservations. When you unify those concepts, failures become predictable and recoverable instead of mysterious.

Decision Guidance: When an RCS Is a Strong Fit (And When It Isn’t)

You likely need an RCS when…

You have competing work priorities, shared travel space, or growth plans beyond a small pilot. If a facility is moving from a handful of robots to a real fleet, robot scheduling becomes less about dispatching and more about policy. The moment you care about robot traffic control, deadlock prevention, or mixed fleet scheduling, you are already in RCS territory.

You may not need a full RCS when…

If your operation is a simple point-to-point run with very low traffic density and minimal integration needs, a lighter control approach may be adequate—especially if you are intentionally running a short pilot. The risk is not that you “overbuy software.” The risk is that you build process expectations around a small-scale control model, then discover it doesn’t generalize to production volume.

A disciplined approach is to define a “scale trigger” upfront. For example, once robots exceed a certain count, once elevators are added, or once multiple robot types enter the same area, you commit to centralized control.

What to Look for in Real-Time Control Performance

In dense operations, responsiveness is not a nice-to-have. It is the difference between smooth flow and constant micro-stops. Wesar’s own discussion of RCS-2000 highlights real-time data handling, noting processing rates over 100 Hz and response under 50 milliseconds as meaningful in high-density environments.

Even if your exact numbers differ by site and integration depth, the evaluation principle holds: you should test for “control-loop behavior,” not just navigation. Ask what happens when a worker steps into an aisle. Ask what happens when two robots approach a narrow passage. Ask how quickly tasks get reassigned when a robot goes offline. Those answers are what determine whether your fleet feels reliable to the people who share space with it.

For more detail on capabilities and positioning, you can reference Wesar’s RCS-2000 dispatching and control capabilities in the context of larger software platform deployments.

About Wesar Intelligence Co., Ltd.

威萨智能股份有限公司有限公司。 positions itself as a one-stop intelligent factory solution provider structured around two core business branches. The first focuses on smart warehousing solutions, including green intelligent logistics robots and the design and implementation of intelligent factory systems. The second provides specialized services for electronics and machinery industries, supported by a 5,000㎡ production facility and a team of over 100 professionals, including production staff and technical experts.

That structure matters for buyers because RCS software success is rarely about software alone. It depends on how well task models, robot behavior, site constraints, and implementation practice come together as a working system.

结论

A Robot Control System is the control plane that turns automation intent into reliable daily execution. When it is designed and deployed with real facility constraints in mind—traffic, stations, exceptions, elevators, and growth—it becomes the difference between “robots that move” and “automation that performs.” If your goal is scalable intralogistics, evaluate RCS software not by feature lists, but by how it handles congestion, exceptions, integration events, and decision latency under real load. Wesar’s RCS-2000 positioning, including centralized task assignment, scheduling, route planning, and coordination with access control and elevators, aligns directly with the operational realities that determine success.

常见问题

What is Robot Control System (RCS) software in warehouse automation?

Robot Control System (RCS) software is a centralized platform that assigns tasks, schedules robots, and plans routes for infield logistics robots. In production environments, it also supports robot traffic control, exception monitoring, and integrations such as access control and elevators.

Is RCS the same as AMR fleet management software?

They overlap heavily. “AMR fleet management software” describes the outcome—managing a fleet—while RCS typically describes the system role in architecture: downstream task execution control, scheduling, and traffic coordination. In most real deployments, the terms converge in practical meaning.

When should I choose an RCS instead of simple AGV dispatching?

If you have higher traffic density, shared intersections, mixed fleets, multi-floor movement, or frequent priority changes, a centralized RCS is usually the more durable choice. Those conditions create congestion and exceptions that basic dispatching tools struggle to manage consistently.

What should I validate during an RCS pilot?

Validate behaviors, not just routes: how the system handles congestion, how it prevents deadlocks, how it recovers from robot downtime, how quickly it reassigns tasks, and how exceptions are surfaced and resolved. If you are considering Wesar’s approach, review the operational scope on the RCS-2000机器人控制系统 page and align pilot tests to those capabilities.